Some tips for GraphQL

Over the last couple of years, GraphQL has popped up in more and more of the projects I've worked on. It's a really cool alternative to REST and is one of my favourite pieces of web development technology to gain traction in recent years.

There are a lot of blog posts out there that'll try to sell you on it. Chances are you've read some of them already. So I won't attempt to do the same here: instead, this article is a collection of tips that have helped me to "think in GraphQL" and get the most out of it.

The first few sections are about schema design. The others focus on leveraging GraphQL effectively in the frontend.

Tip #1: everything is a noun

When designing your Query interface, I recommend naming fields using plain nouns (like users), rather than verb phrases (like listUsers).

This is the most subjective point I'll make in this entire post, so it might be a bold one to kick off with. But it's one of the first mental tricks that started to make GraphQL click for me, so I think it's a good place to start.

You might have seen that verb-based naming style out in the wild. It tends to look like this.

type Query { # This looks kind of like a REST API, if you # squint hard enough. listUsers: [User!]! # GET /users getUser(id: ID!): User # GET /user/:id listBlogPosts: [BlogPost!]! # GET /blog-posts}

type User { id: ID! name: String friends: [User!]! blogPosts: [BlogPost!]!}This has a familiar feeling when coming over from REST: you can see how root schema fields play a similar role to endpoints in traditional web services.

Despite the fact that this analogy can initially help you to wrap your head around GraphQL, I recommend against this naming style in the long run.

Instead, I'd suggest the style seen over on the official GraphQL site, where every field is just a plain noun, all the way to the Query root.

type Query { # Here, the similarity between "users" and "friends" # is clearer. They're both just _things_ you # can request from the web of objects. users: [User!]! user(id: ID): User blogPosts: [BlogPost!]!}

type User { id: ID! name: String friends: [User!]! blogPosts: [BlogPost!]!}There's no technical difference between these two examples, of course. But for me, the second design establishes the mental model of GraphQL much more clearly: every field is "just data", and top-level fields are only special in that they act as entry points into the web of objects. Fully embracing this way of thinking can help you break ties with REST, illuminating new strategies for API design.

For example, in GraphQL, clients can query from multiple resources in a single round trip, and the response might be a mixture of errors and successes. If you don't truly think of your data in terms of a graph, it's easier to end up building an overly rigid interface that neglects that kind of use case.

# Your clients aren't necessarily going to request one# resource at a time. Allow them the flexibility to# do so. Visualise each query as a selection from# the graph of all data objects, rather than thinking# in terms of individual resources.query myCoolQuery { blogPosts { id name }

someUser: user(id: 30) { id name }

# Maybe user 14 doesn't exist, and this data doesn't get # resolved properly. # # In REST, we'd consider this a failed request, and would # return a 404 status code. # # In GraphQL, partial failure should be embraced, and # different error handling strategies should be left open # for the client to choose from. anotherUser: user(id: 14) { id name }}Nesting is also a much more powerful mechanism for modelling relations than it is in REST. This is another place where "thinking in REST" can blind you to alternative approaches offered by GraphQL.

# Thinking RESTfully might surface this interface idea, where# a filter parameter is used to narrow down posts by user.# It's similar to how you'd use query params in a GET# request.type Query { listBlogPosts(byUser: ID!): [BlogPost]}

# There's nothing wrong with that interface: it might even be the# best option for the use case. But if you're not truly thinking in# terms of a graph, you might overlook the alternative option of a# related `blogPosts` field for each user.query myCoolNestedQuery { user(id: 12) { blogPosts { id name } }}All of these concepts are easier to keep in mind when you think of schema fields as objects rather than operations: as nouns rather than verbs.

Names are just names, and you should ultimately use what works for you and your team. But for me, this simple convention provides a surprisingly powerful psychological nudge towards a better understanding of new ways of doing things. Maybe it can do the same for you.

Tip #2: don't wait, paginate

Notice how in that example above, lists of objects were modelled in a direct way? For example, users was just a raw list of User objects.

type Query { users: [User!]!}That's the clearest way to model relations when you're writing about GraphQL on your blog (hi 👋), or when you're drafting a schema on a whiteboard. But real world apps need pagination, and pagination makes the interface for querying lists a little more indirect in practice.

A common pagination pattern in GraphQL is the connections specification. Querying a schema that implements connections looks like this:

query myCoolQuery { # Pagination parameters are added to the field: # here we query for a maximum of 20 users, starting # with user 10. users(first: 20, after: 10) { # In the connections spec, list items are wrapped # in an edges -> node structure. edges { # The actual user data lives in here. node { id name }

# Edges contain metadata to help clients like Relay # understand where we're currently pointing to # in the list. pageInfo { endCursor hasNextPage } }

# The connection provides a place to add custom # metadata too. The total number of users in the # system might be a useful piece of data to # display in the UI, for instance. # # Note how it's tricky to find a nice home for # this data without a solid pagination structure # in place already. totalCount }}This particular pagination pattern is one I'd recommend, as a side note.

If you haven't seen connections before, they might look convoluted at first glance. But it's a widely used standard, so it should be familiar to other developers with GraphQL experience. You'll also be paving the way for proper Relay support by choosing this pagination style.

You'll almost certainly have to add pagination at some point. And if you don't ship it upfront, all consumers are going to have to change the shape of every query involving a list when you do get there. It goes without saying that lists are a pretty common data shape in APIs. So that churn has a significant cost. For that reason, you're typically much better off building with pagination in mind upfront.

Consider doing this even if handling larger amounts of data is considered "not MVP" for your project 👀

It may not even be much extra effort. Python's Graphene already ships with an implementation of connections. For users of that library, supporting pagination is largely just a case of picking the right type of field when defining the schema and its resolvers.

Tip #3: always return an id

Unless you have a compelling reason not to, always provide an id field in both query and mutation results.

Here's an example schema that gets it subtly wrong.

type Query { user(id: ID!): User}

type Mutation { updateMyUser(user: UpdateMyUserInput!): UpdateMyUserResult}

# ✅ Querying a user returns their `id`. That's good.type User { id: ID! name: String}

type UpdateMyUserInput { name: String!}

# ⚠️ Note how for some reason, the user ID is called# `userId` in the mutation result, even though it's# just `id` elsewhere in the schema.type UpdateMyUserResult { userId: ID! name: String}Even worse is to not return the id at all, or to leave the updated data out of the mutation response.

# ⚠️ "The frontend already knows what data was# passed to the mutation, so let's just say# whether or not it succeeded. That should be# enough info, right?"## There's logic behind this line of thought,# but in practice this creates more work# in the frontend.type UpdateMyUserResult { ok: Boolean!}The best mutation responses provide an id field along with the full set of User fields.

# ✅ This is more like it :)type UpdateMyUserResult { id: ID! name: String}To see why this is the way to go, let's step into the shoes of a frontend developer.

Apollo Client is a popular GraphQL library. Its default caching behaviour makes light work of features that might otherwise require a bit of manual wiring of UI state.

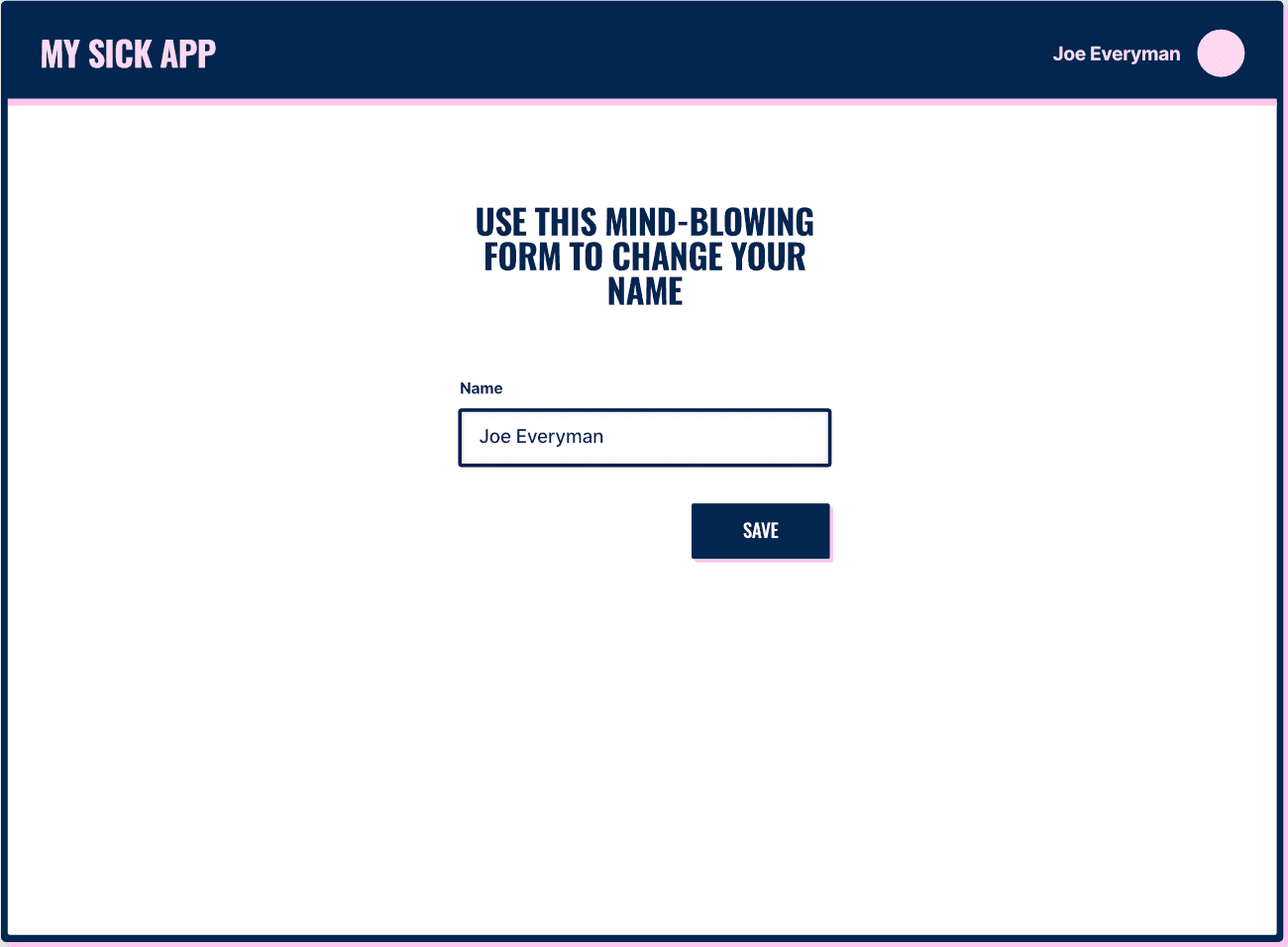

To illustrate this, let's imagine building an "update my name" feature in a hypothetical app. Our designer hands us this mockup of the feature.

Note how the user's name is displayed in the nav bar too. The app will feel broken if that's not also updated after save, so we need to make sure that piece of data is kept in sync.

A typical solution to this problem is to hold the user data in global state, have both components read from the same piece of state, then update that state with the new data after the mutation succeeds.

But Apollo Client can solve this for us instead. It features a built-in data cache, and it automatically updates cached objects after successful mutations. But it can only do that if the mutation response provides the object's id, along with its changed data. If the server doesn't provide those, the frontend can't query for them, and your UI code is left to re-invent the wheel to avoid data synchronisation bugs.

The field doesn't strictly need to be called

id: Apollo can be configured to expect IDs in a different field instead. But a consistent field name is easiest to work with, andidis the default. So unless you have a compelling reason not to, it's best to stick with that.

Tip #4: one user event, one network request

The focus will be on the frontend from here on out, so let's talk about designing good spinner sequences (everyone's favourite topic 🌝).

Often, it's much cleaner for a single user event to trigger a single pending state when new data needs to be fetched.

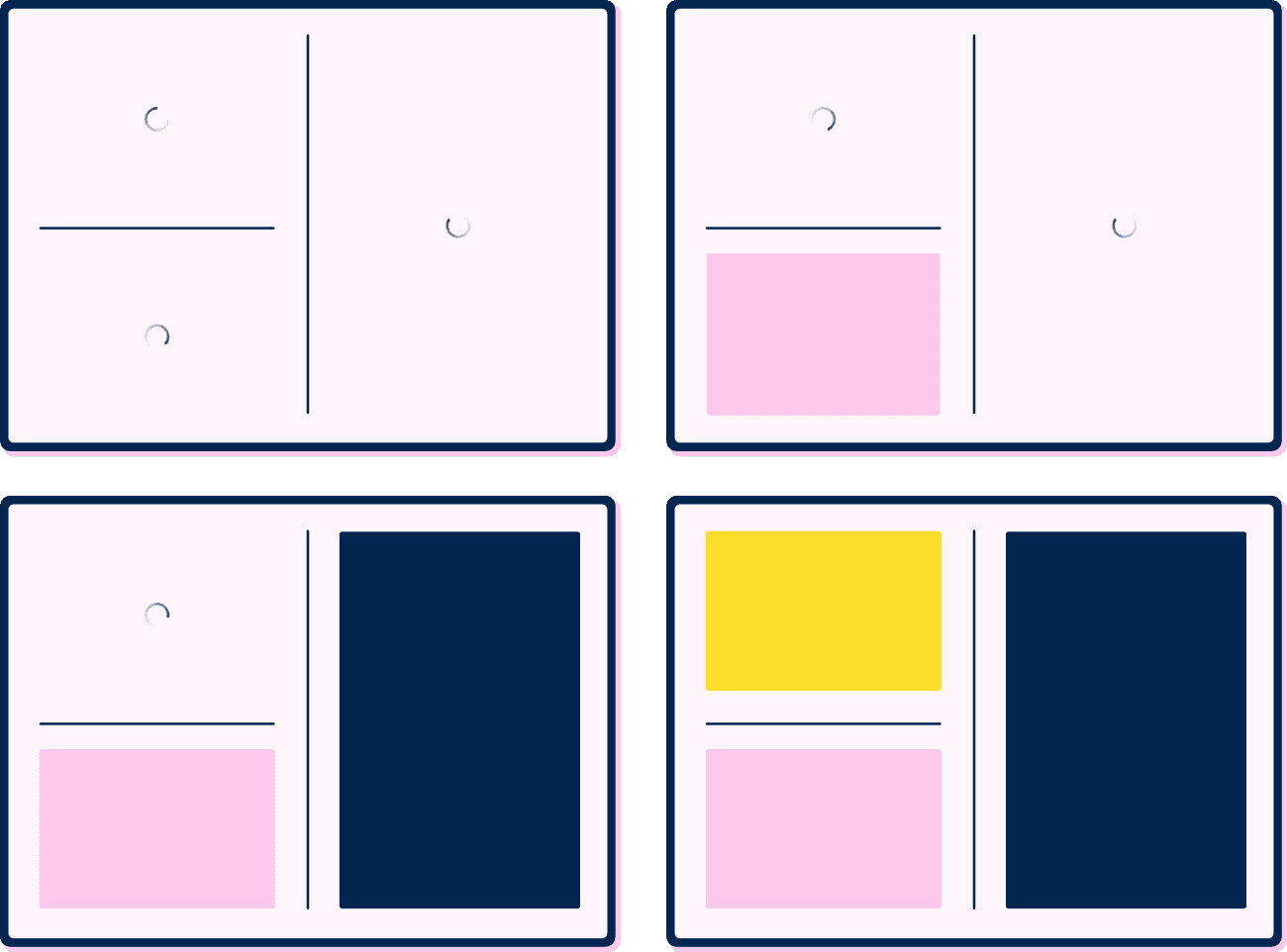

For example, clicking a link is a user event. That event triggers the need to request the data to populate the new page. If different parts of the page finish loading at different times, things can feel bumpy, since the user sees many intermediate states along the way to the final loaded page.

Here, it might feel cleaner to use a single spinner instead, waiting for all three pieces of data to arrive before rendering the final assembled page.

Since a key feature of GraphQL is the ability to fetch multiple resources from the same query, we can bundle together the required data in a single round trip and avoid this spinner hell.

This sounds straightforward enough, but in practice, it's surprisingly easy to end up writing code that doesn't follow this pattern.

A common trap in React is to make each component in the tree responsible for fetching the data it displays. This seems like a nice separation of concerns at first glance, since each component only cares about the data it directly renders.

function MyPage() { return ( <div> <Sidebar /> <UserList /> </div> );}

// This example uses Apollo Client.// Each of the <Sidebar /> and <UserList /> components// fetches its own data with the useQuery() hook.function Sidebar() { const { data, loading } = useQuery(SIDEBAR_QUERY);

if (loading) { return <Spinner />; }

// ...}

function UserList() { const { data, loading } = useQuery(USERS_QUERY);

if (loading) { return <Spinner />; }

// ...}However, doing this splits the data fetching for <MyPage /> across multiple parallel requests that will resolve at different times.

A single larger query higher up the component tree instead could improve the perceived performance by reducing the number of loading sequence steps, as well as potentially improving the actual performance too, by bundling multiple data fetches into a single network round-trip.

function MyPage() { // Here, MY_PAGE_QUERY includes both the data needed // for the sidebar as well as the user list data. const { data, loading } = useQuery(MY_PAGE_QUERY);

// This is now the lone spinner in the loading sequence. if (loading) { return <Spinner />; }

// <Sidebar /> and <UserList /> now render data based on props // instead of fetching their own data. return ( <div> <Sidebar info={data.sidebarInfo} /> <UserList users={data.users} /> </div> );}Tip #5: don't split queries by resource

One way of summarising the previous section is: don't split queries across component boundaries without considering the impact it may have on user experience.

This section looks at another common approach to query splitting that can lead to similar outcomes: splitting queries by resource.

Inevitably different parts of your app will need the same bit of data. Two different pages will list out the same blog posts. Or, a list of users will appear in ten different places in the UI. It can be tempting to refactor the duplication away by gathering queries together, one query per resource.

src/

queries/

blogPostsQuery.js

usersQuery.js

...My advice is not to do this. Let's consider a concrete scenario where this code structure can have unintended side effects.

One day, a feature request comes in to display the number of likes next to each blog post in a web app you're working on. The blog posts are displayed in a couple of different places throughout the site, but we only want to show the likes in <BlogPage />.

The current code looks like this.

// queries/blogPostsQuery.jsconst BLOG_POSTS_QUERY = gql` query blogPosts { blogPosts { id name } }`;

// components/BlogPage.js//// (This is the component we'd like to modify)function BlogPage() { const { data } = useQuery(BLOG_POSTS_QUERY);

return ( <div> {/* some code to render the blog posts */} </div> );}

// components/CompanyPage.js//// (This is another component that happens to render// the same blog posts)function CompanyPage() { const { data } = useQuery(BLOG_POSTS_QUERY);

// ...}One quirk of our system is that in the backend, for one reason or another, it happens to be slower to fetch the likes field than the other blog post fields. Maybe the data for likes lives in an external API and additional network overheads are incurred between backend services in order to resolve the field.

In any case, we want to add the feature, so we go ahead and add the likes field to the shared blogPostsQuery.js file and make our changes to <BlogPage /> to render the new data.

// queries/blogPostsQuery.jsconst BLOG_POSTS_QUERY = gql` query blogPosts { blogPosts { id name likes } }`;

// components/BlogPage.jsfunction BlogPage() { const { data } = useQuery(BLOG_POSTS_QUERY);

return ( <div> {/* The rendering code changes: the `likes` property is read and rendered for each item in data.blogPosts */} </div> );}

// components/CompanyPage.js//// This component doesn't need to change, since likes// aren't displayed here.function CompanyPage() { const { data } = useQuery(BLOG_POSTS_QUERY);

// ...}The subtle problem with this new version of the code is that the company page now overfetches.

Since BLOG_POSTS_QUERY is shared between both pages, the company page asks the server for the likes field too, even though it doesn't display that data. An unrelated component has just taken an unnecessary performance hit.

Another version of this problem can crop up when using fragments to DRY up queries across pages.

Fragments can be useful, but you should make sure that queries sharing the same fragment really do need all of the same fields. It's easy to overuse fragments to tidy up apparent duplication between queries that actually end up with diverging requirements later down the line.

Another common side effect of the query-per-resource approach is the use of separate network requests to fetch multiple resources.

// We already have these queries. Might as well// reuse them for a page that displays both bits// of data, right?import usersQuery from "queries/usersQuery";import blogPostsQuery from "queries/blogPostsQuery";

function SomePageComponent() { // Splitting queries by resource type makes this approach // seem logical. But now there are two network requests, // one from each useQuery() call. // // More importantly, there are multiple pending states to be // concerned with too, so code complexity is increased. const { data: usersData, loading: usersLoading } = useQuery(usersQuery); const { data: blogPostsData, loading: blogPostsLoading } = useQuery(blogPostsQuery);}My advice here is: there's nothing wrong with just writing a new query from scratch for each page. There will probably be some duplication across your queries, and that's okay. At least the data loaded by each page will be clear and explicit, and can't be inadvertently impacted by changes elsewhere in the app.

A common theme

If there's something that underpins this whole article, it's essentially this: avoid designing code in a way that undermines GraphQL's benefits.

Those benefits are probably what sold someone on using it in your project in the first place. But it's easier than you might expect to find yourself writing code that artificially recreates the limitations of REST.

A bit of extra care can help you build a system that works seamlessly with libraries to ease the burden of common web app development concerns such as client-side caching, pagination and loading sequence design.